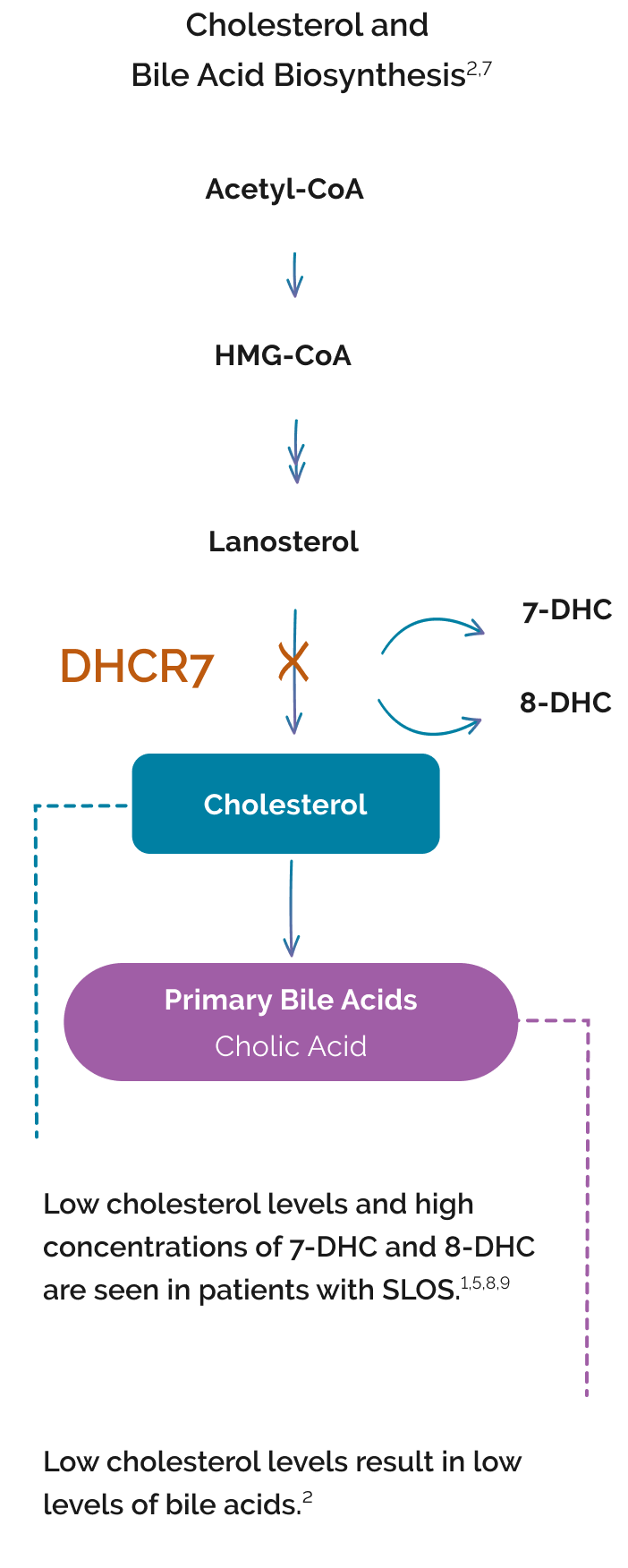

SLOS results from an autosomal recessive mutation on the 7‑dehydrocholesterol reductase (DHCR7) gene.1-3

Deficient activity of DHCR7 impairs the final step in cholesterol biosynthesis.4 This results in:

- Low cholesterol levels1,5

- A buildup of toxic cholesterol precursors 7‑DHC (7‑dehydrocholesterol) and 8‑DHC (8‑dehydrocholesterol)4,5

Bile acids are also impacted because cholesterol is needed for bile acid synthesis.1,6

Patients with SLOS can present with broad clinical manifestations1,8,10

Clinical SLOS phenotypes may include major and minor malformations1,5:

Increase in toxic cholesterol precursors 7‑DHC and 8‑DHC1,5,7

Decrease in cholesterol production and absorption4,11

- Interference with embryonic development (hedgehog signaling)8

- Altered vitamin D synthesis4,5

- Effects on cell membranes/myelin, lipid rafts1,4

- Deficiencies in steroid hormones, bile acids, and oxysterols1,5,12

Decrease in primary bile acids12

- Primary bile acids are critical for4,6,13:

- Absorption of fat and fat-soluble vitamins

- Increased absorption of cholesterol

- A decrease in bile acids may lead to poor nutrition and poor growth12

INDICATIONS AND LIMITATIONS OF USE

CHOLBAM® (cholic acid) is a bile acid indicated for

•

Treatment of bile acid synthesis disorders due to single enzyme defects.

•

Adjunctive treatment of peroxisomal disorders, including Zellweger spectrum disorders, in patients who exhibit manifestations of liver disease, steatorrhea, or complications from decreased fat-soluble vitamin absorption.

LIMITATIONS OF USE

The safety and effectiveness of CHOLBAM on extrahepatic manifestations of bile acid synthesis disorders due to single enzyme defects or peroxisomal disorders, including Zellweger spectrum disorders, have not been established.

IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION

WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS – Exacerbation of liver impairment

•

Monitor liver function and discontinue CHOLBAM in patients who develop worsening of liver function while on treatment.

•

Concurrent elevations of serum gamma glutamyltransferase (GGT) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) may indicate CHOLBAM overdose.

•

Discontinue treatment with CHOLBAM at any time if there are clinical or laboratory indicators of worsening liver function or cholestasis.

ADVERSE REACTIONS

•

The most common adverse reactions (≥1%) are diarrhea, reflux esophagitis, malaise, jaundice, skin lesion, nausea, abdominal pain, intestinal polyp, urinary tract infection, and peripheral neuropathy.

DRUG INTERACTIONS

•

Inhibitors of Bile Acid Transporters: Avoid concomitant use of inhibitors of the bile salt efflux pump (BSEP) such as cyclosporine. Concomitant medications that inhibit canalicular membrane bile acid transporters such as the BSEP may exacerbate accumulation of conjugated bile salts in the liver and result in clinical symptoms. If concomitant use is deemed necessary, monitoring of serum transaminases and bilirubin is recommended.

•

Bile Acid Binding Resins: Bile acid binding resins such as cholestyramine, colestipol, or colesevelam adsorb and reduce bile acid absorption and may reduce the efficacy of CHOLBAM. Take CHOLBAM at least 1 hour before or 4 to 6 hours (or at as great an interval as possible) after a bile acid binding resin.

•

Aluminum-based Antacids: Aluminum-based antacids have been shown to adsorb bile acids in vitro and can reduce the bioavailability of CHOLBAM. Take CHOLBAM at least 1 hour before or 4 to 6 hours (or at as great an interval as possible) after an aluminum-based antacid.

PREGNANCY

No studies in pregnant women or animal reproduction studies have been conducted with CHOLBAM.

LACTATION

Endogenous cholic acid is present in human milk. Clinical lactation studies have not been conducted to assess the presence of CHOLBAM in human milk, the effects of CHOLBAM on the breastfed infant, or the effects of CHOLBAM on milk production. The developmental and health benefits of breastfeeding should be considered along with the mother’s clinical need for CHOLBAM and any potential adverse effects on the breastfed infant from CHOLBAM or from the underlying maternal condition.

GERIATRIC USE

It is not known if elderly patients respond differently from younger patients.

HEPATIC IMPAIRMENT

•

Discontinue treatment with CHOLBAM if liver function does not improve within 3 months of the start of treatment.

•

Discontinue treatment with CHOLBAM at any time if there are clinical or laboratory indicators of worsening liver function or cholestasis. Continue to monitor laboratory parameters of liver function and consider restarting at a lower dose when the parameters return to baseline.

OVERDOSAGE

Concurrent elevations of serum GGT and serum ALT may indicate CHOLBAM overdose. In the event of overdose, the patient should be monitored and treated symptomatically. Continue to monitor laboratory parameters of liver function and consider restarting at a lower dose when the parameters return to baseline.

Please see full Prescribing Information for additional Important Safety Information.

References: 1. Porter FD. Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16(5):535-541. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2008.10 2. Tint GS, Irons M, Elias ER, et al. Defective cholesterol biosynthesis associated with the Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(2):107-113. doi:10.1056/NEJM199401133300205 3. Jezela-Stanek A, Siejka A, Kowalska EM, Hosiawa V, Krajewska-Walasek M. GC-MS as a tool for reliable non-invasive prenatal diagnosis of Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome but essential also for other cholesterolopathies verification. Ginekol Pol. 2020;91(5):287-293. doi:10.5603/GP.2020.0049 4. DeBarber AE, Eroglu Y, Merkens LS, Pappu AS, Steiner RD. Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2011;13:e24. doi:10.1017/S146239941100189X 5. Griffiths WJ, Abdel-Khalik J, Crick PJ, et al. Sterols and oxysterols in plasma from Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome patients. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2017;169:77-87. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2016.03.018 6. Staels B, Fonseca VA. Bile acids and metabolic regulation: mechanisms and clinical responses to bile acid sequestration. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(suppl 2):S237-S245. doi:10.2337/dc09-S355 7. Shefer S, Salen G, Batta AK, et al. Markedly inhibited 7‑dehydrocholesterol-delta7-reductase activity in liver microsomes from Smith-Lemli-Opitz homozygotes. J Clin Invest. 1995;96(4):1779-1785. doi:10.1172/JCI118223 8. Ballout, RA. Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome (SLOS). In: Rezae N, ed. Genetic Syndromes. Springer, Cham. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66816-1_501-1 9. Kelley RI, Hennekam RCM. The Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome. J Med Genet. 2000;37(5):321-335. doi:10.1136/jmg.37.5.321 10. Steiner RD, Rohena LO. Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome. Medscape. Updated September 24, 2021. Accessed January 4, 2023. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/949125-print 11. Ying L, Matabosch X, Serra M, Watson B, Shackleton C, Watson G. Biochemical and physiological improvement in a mouse model of Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome (SLOS) following gene transfer with AAV vectors. Mol Genet Metab Rep. 2014;1:103-113. doi:10.1016/j.ymgmr.2014.02.002 12. Honda A, Salen G, Shefer S, et al. Bile acid synthesis in the Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome: effects of dehydrocholesterols on cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase and 27-hydroxylase activities in rat liver. J Lipid Res. 1999;40(8):1520-1528. 13. Schmidt DR, Holmstrom SR, Fon Tacer K, Bookout AL, Kliewer SA, Mangelsdorf DJ. Regulation of bile acid synthesis by fat-soluble vitamins A and D. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(19):14486-14494. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.116004